The example of a house in Ain between history and genealogical research

Following the French Revolution, between 1790 and 1795, time was intuitively symbolised by a candle during the sales of national goods.

These assets, confiscated by the State, were seized and then sold at auction during public sessions called "adjudications".

Historical context

Which goods are affected?

- The national assets of primary origins that were seized following the nationalisation of Church property from the decree of November 1789 and their sale in May 1790. These are the assets of the clergy (abbeys, convents, lands, and buildings in the possession of the religious).

- The national goods of second origins were sold from 1792 and 1793. These were seized from emigrants and political prisoners who left France at the beginning of the French Revolution.[1]The social origin of these emigrants is revealing: about 25% came from the clergy and 17% from the nobility. The majority therefore belonged to the Third Estate, mainly consisting of bourgeois and peasants who were anxious about the excesses of the Revolution.[2].

- The "fire" auction took place during a public session. The process of the sale was as follows:

- An inventory of the asset is drawn up by the local administration, which is also referred to as the departmental directorate

- The asset is valued by experts who assign it a value.

- Advertisements of the time were published in the form of posters.

- Small candles (or lights) are successively lit.

- Each candle burns for a few minutes at most.

- As long as the lights are on, citizens can bid; the award is final if no new bid is made when the candle goes out. In some cases, the sale was concluded at the first light if no one outbid.

- Each bid had to be over ten pounds and not exceed one-twentieth of the total amount of the last bid.

- The buyer pays a deposit and then the remainder with assignats. The payment can be spread over several years.

What are assignats used for?

It is in this context that the assignats, convertible into gold, appear and are used to acquire national assets. They do not have a monetary value at the beginning but are used as mortgage bonds. Their rise begins on 19 December 1789 and then develops rapidly with increasing issues to meet financial needs and exchanges. It is in December 1796, after a cumulative issue of 45 billion livres, that the issuance of assignats ceases. The reason is a depreciation, inflation, and a lack of confidence among users regarding metallic currency. [3].

Photograph of a fifteen-sols assignat.

The case of Jean Claude Meynier

The first step is to look at the register of goods seized during the Revolution. It is located in series 1Q and lists all the second-origin goods sold in Ain.

Extract from the AD01 site leading to the register of emigrants' property (2nd origin).

Let us follow a concrete case that takes place in Ain, during the session of 21 Frimaire Year II, on 11 December 1793. The minutes of adjudication, sale books, and registers of the assets seized during the revolution are kept in the departmental archives in series 1Q. However, during my visit to the archives, the minutes of the sale adjudication were kept under the provisional reference V2/47 as the documents were in the process of being classified.

Initially, the board of the Ain department drafts the articles[4] that frame the legislation on sales. The conditions described were generally similar to national laws, but there could be local specificities such as the initial payment period, the distribution of costs, or the publication procedures.

The directory imposes on the buyer a staggered payment of the purchase price of national goods, with an initial payment of administrative fees within eight days. Furthermore, a deposit of 10% without interest is due in the month following the award. The balance is spread over ten annual instalments, with interest at 5% on the remaining capital due.

The possession of the property can only be taken after these initial payments. The rents of the property are only acquired from the date of sale. The buyer assumes the existing easements without compensation and must pay the registration fees.

The assets are transferred without any specific guarantee regarding their size or value, except in legal cases. They are conveyed free from any prior commitments, such as debts, annuities, or mortgage charges. This system aims to simplify and secure the transaction, while allowing the buyer to make a gradual and accessible payment.

During this session on 11 December 1793, ten properties were put up for sale, one of which, a house dating back to at least 1782, still exists today. This place, rich in history, is one of the first properties of secondary origin listed among the 311 sold in the district of Bourg.

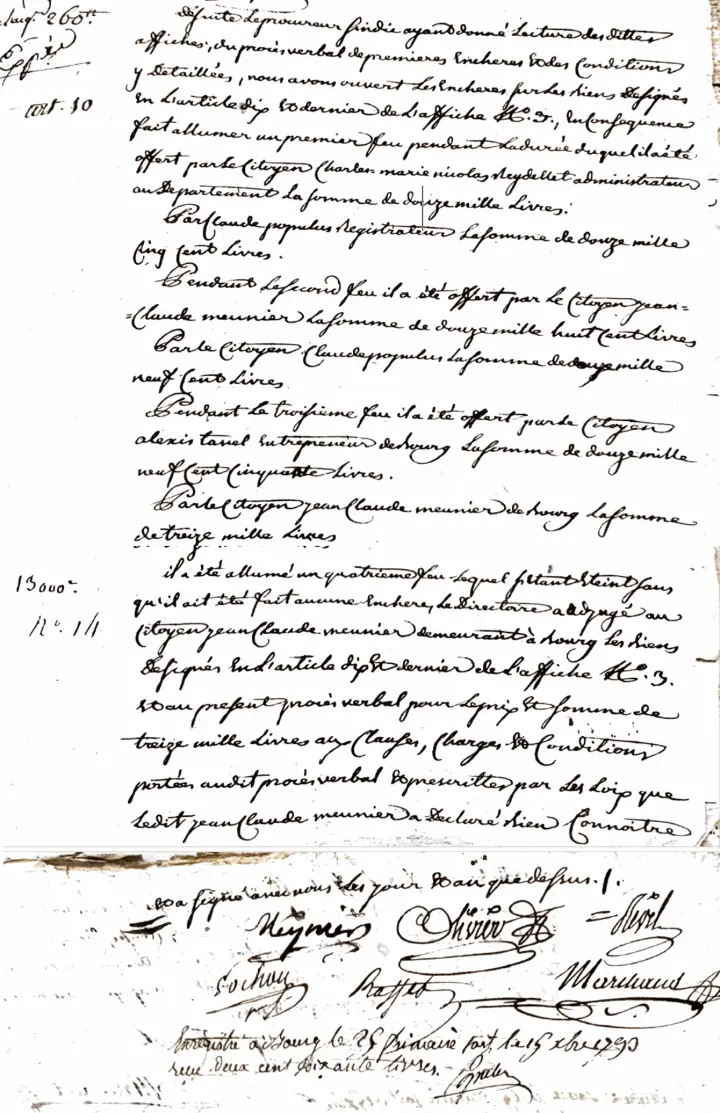

This sale[A] begins with the bid of Charles Marie Nicolas Reydellet, administrator of the department, at a value of 12,000 livres.

At the second round, Jean Claude Meynier offers 12,800 livres, followed by Claude Populus with a bid of 12,900 livres.

At the third auction, Alexis Tavel offers 12,950 livres, then Jean Claude Meynier returns with a bid of 13,000 livres.

Finally, during the fourth bidding round, no other bidders come forward, and the sale is awarded to the last named. The signature of the buyer "Meynier" is affixed at the bottom of the page.

Personal photograph taken at the back of the house, August 2024.

What was the social background of the buyers?

For ecclesiastical property, half of the buyers were peasants, but they only acquired small plots (less than 5 hectares), while the upper bourgeoisie appropriated the large estates.[5].

Regarding the property of emigrants and political prisoners, the social origin of the buyers varied depending on the regions. While some rural departments show a significant number of peasants as buyers[6]Others, like Finistère, show that these sales benefited the bourgeoisie of small towns as well as the families of former emigrants who remained in the area, sometimes competing with the direct heirs. Many buyers also came from neighbouring municipalities, whether they were bourgeois or wealthy farmers.[7] In both cases, it is often the Bourgeoisie that takes possession of the largest plots in terms of area. In certain places like Ardèche, peasant societies were formed collectively and purchased plots.

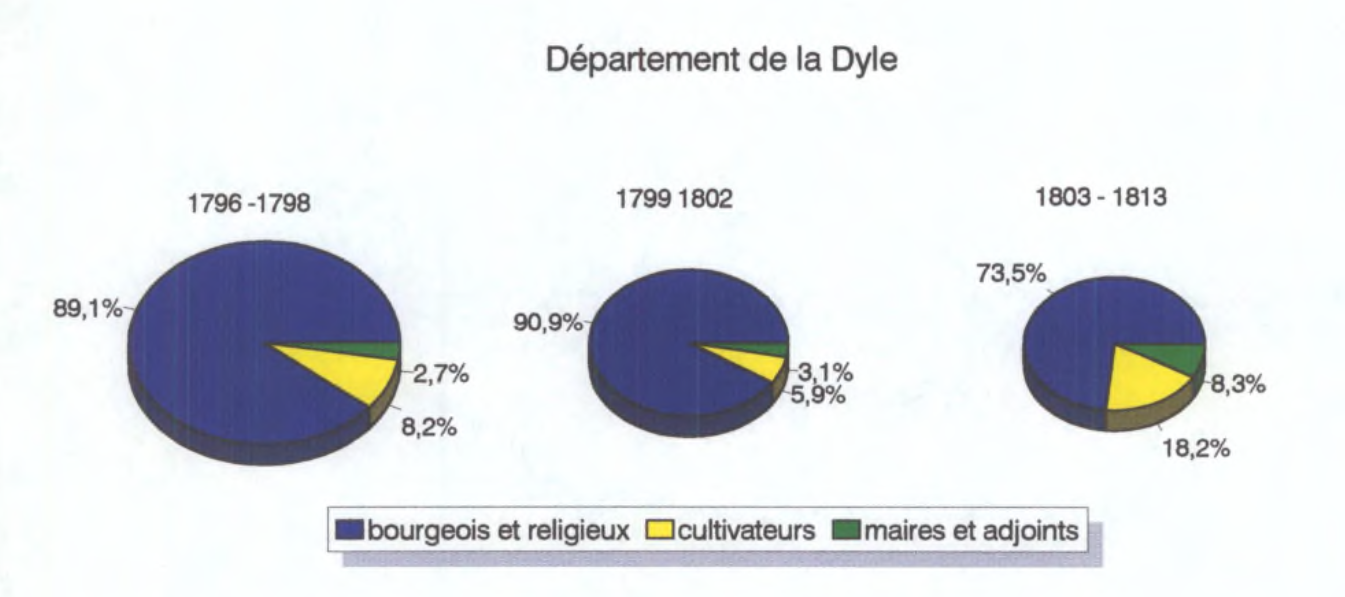

In Belgium, in the department of the Dyle, the bourgeoisie and the financial companies that controlled the market for national goods limited the peasantry in their ability to acquire land. Before the year 1799, farmers were obliged to make arrangements with them. Thus, the farmers managed to become owners of only 8.2% of the national goods sold during the years 1790-1796 compared to 89.1% for the bourgeoisie.[8] It is important to note that the property confiscated from emigrants accounts for only 0.43% of the total national assets alienated in the department of Dyle. This low proportion can be explained by the fact that the Belgian nobility was relatively spared during the republican episode.

Diagram of the distribution of buyers by social origin

François ANTOINE – The sale of national assets in the department of Dyle, page 388/496.

Who is Jean Claude Meynier? How to find his genealogy for free and easily?

In order to familiarise myself with the buyer and understand the social background of this man, I sought to explore his genealogy. To trace his genealogy in the Ain, the parish registers are easily accessible online on the website of the Archives de l'Ain and allow us to learn more about this man.

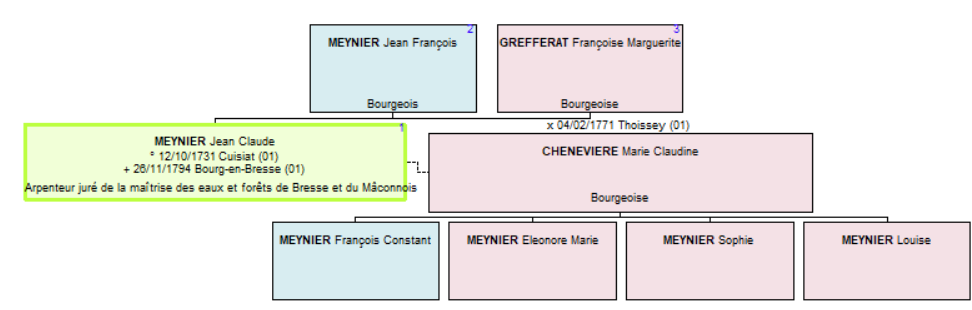

Born in Cuisiat on 12 October 1731, he is the son of Sieur Jean François Meynier, lord and burgher of Cuisiat, and Miss Françoise Marguerite Grefferat, which allows us to attest to the direct lineage and status of his family.

AD01, Birth certificate of Jean Claude MEYNIER, Cuisiat, 1731 - 1735 - (1731 - 1735), LOT33468, view 4/33.

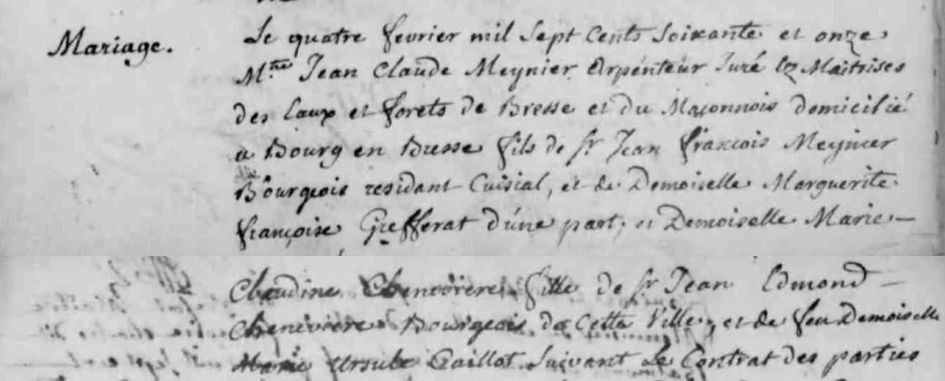

To highlight the roles held by Jean Claude Meynier, he is mentioned at his marriage, on 4 February 1771 in Thoissey, as "sworn surveyor of the management of waters and forests of Bresse and the Mâconnais," residing in Bourg-en-Bresse. The sworn surveyor was a sworn expert responsible for officially measuring and delineating parcels of forests, wooded areas, and lands pertaining to the management of waters and forests, a royal then revolutionary administration. His role was crucial in the management, protection, and regulation of these natural resources. Furthermore, his wife, Marie Claudine Chenevière, also belonged to the bourgeoisie.

AD01, extract from the marriage certificate of Jean Claude Meynier and Marie Claudine Chenevier, Thoissey, 1771 - 1771 - (1771), LOT108219, view 3-4/20.

What is the fate of Jean Claude Meynier?

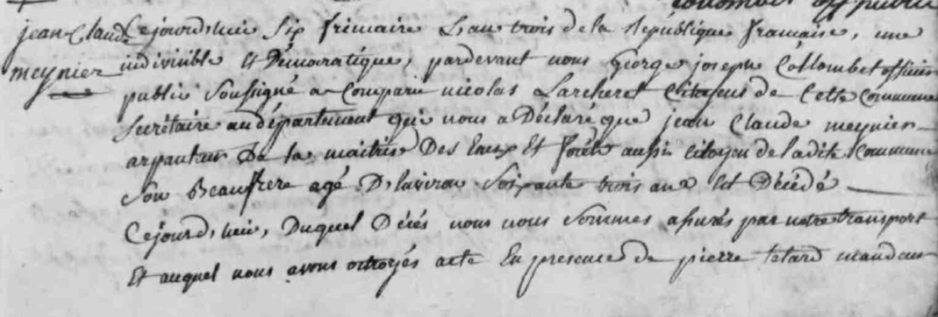

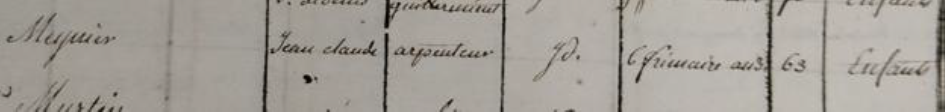

Just under a year after the acquisition, the buyer of the property passed away at the age of 63, on 6 Frimaire Year III (26 November 1794) in Bourg-en-Bresse.

AD01, extract from the death certificate of Jean Claude Meynier, Bourg-en-Bresse, 1794 - 1795 - (Year III), LOT11583, view 13-14/111.

What happens to the estate following their death?

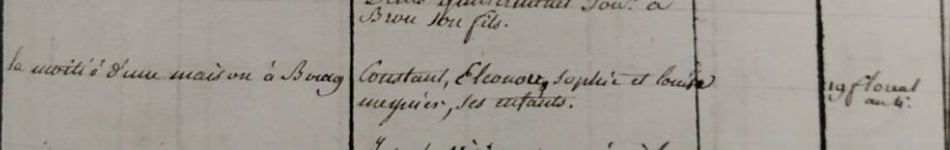

The table of burial extracts and the registers of inheritance by death establish that the declaration of succession and the transfer of the house took place on 19 Floréal Year IV (8 May 1796).

Part 1 :

Part 2 :

AD01, tables of burial extracts, 1789-year VIII, AD01, Volume 4, 3Q 3521.

Following the death of their father, the four children inherit half of the house, valued at 4000 livres. The notarial records reveal a deed of sale carried out by the notary Fontaine on 9 Frimaire Year XII (1 December 1803), ratified on 14 Nivôse following (5 January 1804). The siblings act jointly to resell the house. The ratification of the sale is signed by Marie Claudine Chenevière, widow of the late Jean Claude Meynier, who approves the transaction.

“Elénod-Marie Meynier, a supplementary member in the registration section, Sophie and Louise Meynier […] acting both in their own names and on behalf of François Constant Meynier, their brother […] who in the aforementioned names and jointly without division or discussion to which they renounce, sell to Joseph Lescuyer, a property owner residing in Bourg, here present and accepting, a house, building, courtyard and garden, forming an enclosed area, belonging to the said Meynier brothers and sister, located in Bourg, Rue des Ursules, near the old gate of the Capuchins, which their father acquired from the nation.”

Transcription and translation of a sale between Meynier and Lescuyer, Minutes of Philibert Marie Fontaine and Jean François Morellet, 1st Frimaire to 1st Nivôse Year XII, AD01, 3E 22902.

The information obtained from the various sources allows for the creation of the following family tree:

Family tree of Jean Claude MEYNIER

Family tree of Jean Claude MEYNIER, 2023-asc-complete-colour, Généatique 2024.

Conclusion

This article dedicated to the sale of a national asset in Ain is part of the broader context of revolutionary seizures and illustrates the mechanisms implemented to redistribute the property of the Church and then of emigrants. The specific case of the house acquired by Jean Claude Meynier, a sworn surveyor and member of the local bourgeoisie, is one example among thousands recorded solely in the department of Ain.

The analysis of the social origins of buyers highlights the predominance of the bourgeoisie, even though small peasant ownership also finds its place, depending on regional specificities.

In a forthcoming article, I will propose to shed light on the life of the property's owner during the French Revolution, as well as the complex reasons that led to the seizure of this property by the State and the upheaval of her existence.

A - Minutes of the Auction

Transcription (in French) :

« Article 10

13 000 livres

N °14

Desuite, le procureur syndic ayant donné lecture des dittes

affiches, du procès-verbal de premières enchères et des conditions

cy détaillées, nous avons ouvert les enchères sur les biens désignés

en l’article dix et dernier de l’affiche n°3, en conséquence,

fait allumer un premier feu pendant la durée duquel il a été

offert par le citoyen Charles Marie Nicolas Reydellet, administrateur

au département, la somme de douze mille livres.

Par Claude Populus, registrateur, la somme de douze mille

cinq cent livres.

Pendant le second feu, il a été offert par le citoyen Jean-

Claude Meunier la somme de douze mille huit cent livres.

Par le citoyen Claude Populus la somme de douze mille neuf cents livres.

Pendant le troisième feu, il a été offert par le citoyen

Alexis Tavel, entrepreneur de Bourg, la somme de douze mille

neuf cent cinquante livres.

Par le citoyen Jean-Claude Meunier de Bourg, la somme

de treize mille livres.

il a été allumé un quatrième feu lequel étant éteint sans

qu’il ait été fait aucune enchère, le directeur a adjugé au

citoyen Jean Claude Meunier demeurant à Bourg les biens,

d’après lesdits articles six et dernière de la fiche N°3,

et au présent procès-verbal pour le prix et somme de

treize mille livres aux clauses, charges et conditions

portées audit procès-verbal, souscrit par les lois que

ledit Jean Claude Meunier a déclaré bien connaître

et a signé avec nous les jour et an que dessus »

Sources :

[1] Décret du 28 mars 1793 puis 25 brumaire III (15 novembre 1795) : « Tout Français de l’un et de l’autre sexe qui, ayant quitté le territoire de la République depuis le 1er juillet 1789, n’y était pas rentré au 1er mai 1792 »

[2] Arnaud Decroix, La noblesse en émigration ou la tentative d’une reconstruction politique (1789-1815), p305-318

[3] Le site du collectionneur, - FRANCE - La folle histoire des assignats, Alain Grandjean, 2003

[4] AD01, Vente de biens nationaux provenant d’émigrés, V2-47 (côte temporaire), vue 7-10.

[5] Bernard Bodinier et Eric Teyssier - Les biens nationaux en France : état de la question, p. 87-99

[6] LOUTCHISKY Ivan, Propriété paysanne et vente des biens nationaux pendant la Révolution française. Introduction de Bernard Bodinier et Éric Teyssier, 1895, réédition 1999.

[7] Biens nationaux - Les mémoires de Locronan

[8] François ANTOINE – La vente des biens nationaux dans le département de la Dyle, page 388/496